Newman’s argument hinges upon how the film has been unjustly mistreated by figures that never got to see the original version or who were aware of a longer version, but damned the film regardless. He compares this to the similarly ill-treated cinematic releases of Blade Runner (Dir. Ridley Scott, USA, 1982) and Brazil (Dir. Terry Gilliam, USA, 1982) but whose later, purer versions were ultimately critically acclaimed.

I like Fritz Lang's Metropolis, who doesn't?

You would have to be crazy not to be at least a little intrigued by it!

However, I also pride myself on the fact that I was lucky enough not to see the film until the release of the 2010 rediscovered complete version of Metropolis, so I first experienced it as it was originally intended by Lang.

|

| I saw it at the Little Theatre Cinema, Bath and it was a hugely enjoyable experience - £7.20 well spent! |

A couple of months following the screening at the Little Theatre Cinema I had to produce an analysis of two published reviews for a Film and Screen Studies assignment, as part of the (second) first year of my BA (Hons), and The Complete Metropolis made for the perfect focus.

What I have presented here is that very analysis.

What I have presented below is basically the same as what I originally submitted back in 2010. I have gone through and polished the writing slightly, as I was only just getting to grips with my understanding of English grammar at the time, so my writing style is very clunky throughout.

Additionally, I have employed the wrong academic method for referencing throughout, which I do not bother to correct here. I also have not bothered linking this new post to the reviews and articles discussed, as I have been having some trouble locating them using the original urls, so you will just have to take my word for it.

Ultimately, the piece does not come to any real clearly stated conclusion, but does make a strong point about the freedom and potential available to bloggers, I believe it was the incentive of this point that first got me thinking about starting my own blog.

In all truth, if I was to thoroughly polish this analysis, I would just rewrite it from scratch, but I am not going to do that, as it stands as testimony of how I have developed as a cinephile and an academic.

Being a first year piece of university work, most of the analysis' technical shortcomings were forgiven in favour of how I actually analysed the two reviews. Ultimately, this piece of work was awarded a first.

I hope you enjoy reading it or that it serves of some productive use...

An Analysis of Two Published Reviews

This analysis will concern itself with the deconstruction and evaluation of two film reviews. One review, from Sight and Sound, is written by Kim Newman; while the other is by Bernardo Villela and comes from the blog of FilmSnobbery.com.

Both reviews detail the 2010 re-release of the rediscovered and reconstructed Metropolis (Dir. Fritz Lang, Germany, 1927) or, as some advertising materials have referred to it, The Complete Metropolis.

Throughout this analysis the reviews will be compared and contrasted with one another; as well as to the views of various other reviewers and film theorists.

The trailer for the 2010 release of the recently rediscovered complete version of Metropolis.

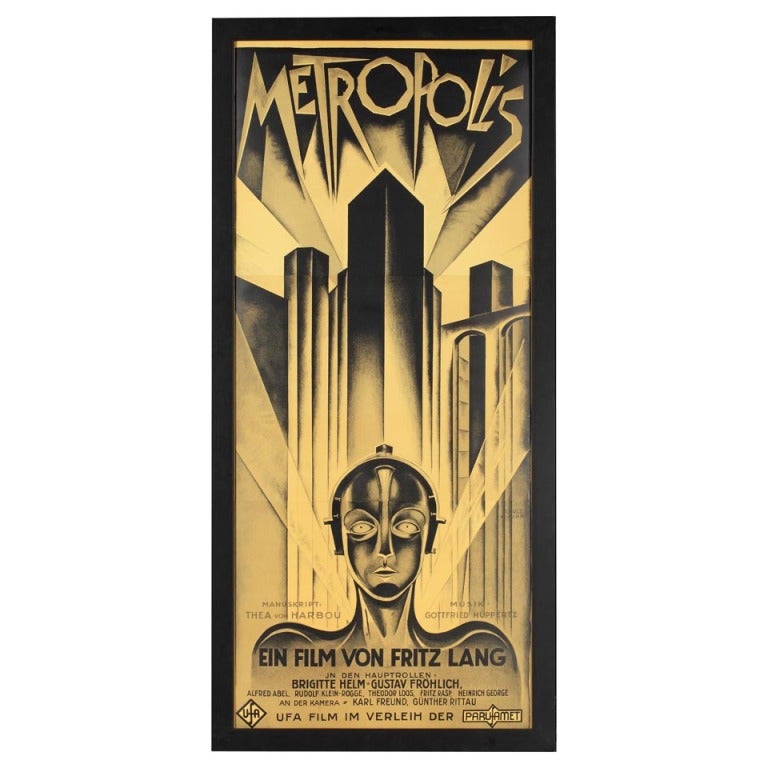

The Complete Metropolis is a cause for celebration with Kim Newman’s review. The review is the issue’s cover story and, as such, has its front cover adorned with the iconic image of the robot. As director Oshii Mamoru comments: ‘Metropolis is one of those rare movies in which one of its characters happens to epitomise the essence of the movie itself.’ (Oshii, Remake Remodel Cityscapes and Robots p. 19).

Gold and gleaming, like an Idol, the robot embodies the presence of a monumental film that everyone, even if they are not knowledgeable about silent cinema, is at least vaguely aware of.

Next to the robot is the headline: ‘Metropolis Reborn’ and under which resides the film’s year of release 1927. But the lack of further information such as the director’s name or even a brief blurb elaborating on the headline indicates that the readership of Sight and Sound will immediately know this film and why it is on the cover.

In addition to this, the magazine’s subtitle: ‘THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE’ and the fact the magazine is published by the British Film Institute demonstrates this is a magazine for the film academic or cinephile. The Newman review is what Timothy Corrigan would class as a critical essay; being something that: ‘falls between the theoretical essay and the review. The writer of this kind of essay presumes that his or her reader has seen or is at least familiar with the film under discussion’ (Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film p.11).

Indeed, the review is a full five page spread, three pages of which comprises the review, and the overall word count of this piece would vastly dwarf that of a review appearing in a periodical.

| Sight and Sound, Volume 20, Issue 10. |

Next to the robot is the headline: ‘Metropolis Reborn’ and under which resides the film’s year of release 1927. But the lack of further information such as the director’s name or even a brief blurb elaborating on the headline indicates that the readership of Sight and Sound will immediately know this film and why it is on the cover.

In addition to this, the magazine’s subtitle: ‘THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE’ and the fact the magazine is published by the British Film Institute demonstrates this is a magazine for the film academic or cinephile. The Newman review is what Timothy Corrigan would class as a critical essay; being something that: ‘falls between the theoretical essay and the review. The writer of this kind of essay presumes that his or her reader has seen or is at least familiar with the film under discussion’ (Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film p.11).

Indeed, the review is a full five page spread, three pages of which comprises the review, and the overall word count of this piece would vastly dwarf that of a review appearing in a periodical.

| The famous robot in Metropolis. |

Newman’s strength is in taking a film that is 83 years old and then makes it relevant and something worth watching for the audience of today. Newman’s argument throughout asserts that: ‘the iconic film experienced by audiences worldwide as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has been a long way from what its director originally intended’ (Newman, Remake Remodel p.17.) and, as such, has been unjustly treated and not properly appreciated over the decades because of this.

A figure that he uses to illustrate this mistreatment is that of another great contributor to science fiction, H.G. Wells: ‘The New York Times hired H.G. Wells, no less, to review the paramount version (which had opened in London) and ran his grumpy, splenetic, resentful, beside-the-point tirade’ (ibid. p.17.).

Newman’s argument hinges upon how the film has been unjustly mistreated by figures that never got to see the original version or who were aware of a longer version, but damned the film regardless. He compares this to the similarly ill-treated cinematic releases of Blade Runner (Dir. Ridley Scott, USA, 1982) and Brazil (Dir. Terry Gilliam, USA, 1982) but whose later, purer versions were ultimately critically acclaimed. While these: ‘epic dystopian visions somehow invite this sort of treatment’ (ibid. p. 17.), their later director’s versions received critical acclaim and The Complete Metropolis is no exception to this rule.

Newman’s pieces of background information, scattered throughout, largely detail the reasons behind why the film was originally truncated and how the footage was rediscovered. While this information may already be known to the reader, its inclusion is warranted because it further reinforces Newman’s argument for viewing The Complete Metropolis and why the complete version is a better film: ‘All things considered, the restored Metropolis is a different film from the one discernible in a multitude of versions since early 1927. Its scenario crafted by Lang’s then wife Thea von Harbou, now almost makes complete sense.’ (ibid. p. 17.)

Finally, Newman allows the film to have a context today by comparing it to reception of an equally ambitions and recently released science fiction film: “Wells’ withering attitude to Lang’s film probably resembles the way contemporary science-fiction writers feel about Avatar.” (ibid. p.17). This comparison allows the reader to understand, if they did not already, what a monumental film Metropolis was when it was first released. Newman is using the context in which Avatar (Dir. James Cameron, USA, 2009) was released to recreate the kind of context that Metropolis would have been released and received in.

A figure that he uses to illustrate this mistreatment is that of another great contributor to science fiction, H.G. Wells: ‘The New York Times hired H.G. Wells, no less, to review the paramount version (which had opened in London) and ran his grumpy, splenetic, resentful, beside-the-point tirade’ (ibid. p.17.).

Newman’s argument hinges upon how the film has been unjustly mistreated by figures that never got to see the original version or who were aware of a longer version, but damned the film regardless. He compares this to the similarly ill-treated cinematic releases of Blade Runner (Dir. Ridley Scott, USA, 1982) and Brazil (Dir. Terry Gilliam, USA, 1982) but whose later, purer versions were ultimately critically acclaimed. While these: ‘epic dystopian visions somehow invite this sort of treatment’ (ibid. p. 17.), their later director’s versions received critical acclaim and The Complete Metropolis is no exception to this rule.

| The Complete Metropolis poster. |

Newman’s pieces of background information, scattered throughout, largely detail the reasons behind why the film was originally truncated and how the footage was rediscovered. While this information may already be known to the reader, its inclusion is warranted because it further reinforces Newman’s argument for viewing The Complete Metropolis and why the complete version is a better film: ‘All things considered, the restored Metropolis is a different film from the one discernible in a multitude of versions since early 1927. Its scenario crafted by Lang’s then wife Thea von Harbou, now almost makes complete sense.’ (ibid. p. 17.)

Finally, Newman allows the film to have a context today by comparing it to reception of an equally ambitions and recently released science fiction film: “Wells’ withering attitude to Lang’s film probably resembles the way contemporary science-fiction writers feel about Avatar.” (ibid. p.17). This comparison allows the reader to understand, if they did not already, what a monumental film Metropolis was when it was first released. Newman is using the context in which Avatar (Dir. James Cameron, USA, 2009) was released to recreate the kind of context that Metropolis would have been released and received in.

Newman’s style throughout is typical of the film academic, in that, his structure is free flowing and his style of writing is constantly at ease especially in his referencing of other texts. Newman is confident that his reader will know what he is talking about but, at the same time, still supplying enough information to fill in the gaps if they don’t. While the review is catering for a cinephile readership, Newman still provides enough information for a non-cinephile to discern his arguments, judgement and recommendation for the film.

Newman, it seems, has written a critical essay, but one which he still wants a non-cinephile to be able to get their teeth into; otherwise why would he bother contextualizing the film for today’s audience?

Newman, it seems, has written a critical essay, but one which he still wants a non-cinephile to be able to get their teeth into; otherwise why would he bother contextualizing the film for today’s audience?

From the opening sentence of Villela’s review: ‘The first thing that needs saying is that there are conventions that need to be acknowledged if you are going to venture out and watch this or any silent film’(6), this is a review targeted at an audience who are not familiar with the conventions of silent cinema. If we are to follow Corrigan's view that: ‘a review aims at the broadest possible audience, the general public with no special knowledge of film’ (Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film p.8.), then Villella’s review is one which is designed to be accessible to any demographic: ‘Accordingly, its function is to introduce unknown films and to recommend or not recommend them’ (ibid. p.8.).

This is exactly what Villella is doing by immediately introducing and explaining the cinematic context in which Metropolis was produced: ‘Silent acting, for example, is by its very nature more demonstrative and over-the-top’(6), he is justifying its perceived absurd style in comparison to the more realistic representation of contemporary cinema. While Villella’s opening sentence may not be exactly snappy it does immediately hook the reader with intrigue. It also allows them to feel comfortable by conveying a smooth transition from the accepted conventions of contemporary cinema to the very different ones of the silent period.

|

| An original Metropolis poster. |

This is exactly what Villella is doing by immediately introducing and explaining the cinematic context in which Metropolis was produced: ‘Silent acting, for example, is by its very nature more demonstrative and over-the-top’(6), he is justifying its perceived absurd style in comparison to the more realistic representation of contemporary cinema. While Villella’s opening sentence may not be exactly snappy it does immediately hook the reader with intrigue. It also allows them to feel comfortable by conveying a smooth transition from the accepted conventions of contemporary cinema to the very different ones of the silent period.

While Villela does go on to discuss the performances of some of the actors, the film’s original score, and especially the reconstruction of the film, he fails to justify why the modern spectator should go and see The Complete Metropolis.

It’s all very well claiming you can go and: “see it sharper and more clearly that you’re likely ever seen it before” (6), but to a modern spectator, the majority of which have no interest in silent cinema, this is not incentive enough.

Really what Villela needs to do is give Metropolis a modern context and make it relevant for today, such as Newman did with the allusion to Avatar being today’s equivalent of Metropolis. Overall, Villela has written a review that offers some interesting observations of the reconstruction but, ultimately, feels incomplete.

| New York City + The Tower of Babel = Metropolis |

It’s all very well claiming you can go and: “see it sharper and more clearly that you’re likely ever seen it before” (6), but to a modern spectator, the majority of which have no interest in silent cinema, this is not incentive enough.

Really what Villela needs to do is give Metropolis a modern context and make it relevant for today, such as Newman did with the allusion to Avatar being today’s equivalent of Metropolis. Overall, Villela has written a review that offers some interesting observations of the reconstruction but, ultimately, feels incomplete.

However, attached to this review is an additional article, written by Villela, entitled: Why a New Cut Matters. This article again explores The Complete Metropolis and it is in this that Villela certainly leans closer to contextualizing it for an audience of today. But, again, he still does not achieve this! While, he does emphasize the importance of why a rediscovery can be interesting : “we always knew there was something missing, there should be something endlessly appealing about newly found cuts of films to any enthusiast of cinema” (7), he fails to justify why anybody, other than a film enthusiast, should go and see it.

On set photograph from Metropolis, Fritz Lang is on the far right.

|

The only likely people who will look at the Film Snobbery blog are film buffs, but for anybody who happens to look at it and is not a film buff: will they really be won over into going to see The Complete Metropolis?

Even Newman’s review went the extra mile of justifying why the reader should go and see it. However, if you are to follow what Warren Buckland has to say: ‘The reviewer’s judgement, writing style and decisions about how much background information and condensed arguments to give the reader, is determined by the projected readership and perceived character of the paper of magazine’(Buckland, Teach Yourself Film Studies p. 155), then Villela has done nothing wrong.

However, to go one step further, surely the format of a blog and freedom of expression it allows warrants a deeper exploration: ‘Bloggers have the advantage over print film reviewers in really free speech: they have no professional responsibilities, or policy interventions to deal with.’ (Fishers, On Critics: Bloggers without boundaries p.19).

Surely, this is the kind of freedom any film reviewer would want?

However, Villela seems not to have realised this and it’s ironic to think that Newman’s review still carries a lot of weight even after it’s been through the hands of an editor, unlike Villela’s. Not only has Villela not done any justice for Fritz Lang’s intended version of Metropolis, he has conformed to the stereotype of the blogger as an ‘amateur’ and has not championed the format of the blog as being something truly unbound and full of potential: ‘The best blogs are defined by this quality: they occupy a space between journalism and academia, between disciplines, between film and other cultural forms, offering a new type of criticism’ (ibid, p.19).

Even Newman’s review went the extra mile of justifying why the reader should go and see it. However, if you are to follow what Warren Buckland has to say: ‘The reviewer’s judgement, writing style and decisions about how much background information and condensed arguments to give the reader, is determined by the projected readership and perceived character of the paper of magazine’(Buckland, Teach Yourself Film Studies p. 155), then Villela has done nothing wrong.

However, to go one step further, surely the format of a blog and freedom of expression it allows warrants a deeper exploration: ‘Bloggers have the advantage over print film reviewers in really free speech: they have no professional responsibilities, or policy interventions to deal with.’ (Fishers, On Critics: Bloggers without boundaries p.19).

Surely, this is the kind of freedom any film reviewer would want?

However, Villela seems not to have realised this and it’s ironic to think that Newman’s review still carries a lot of weight even after it’s been through the hands of an editor, unlike Villela’s. Not only has Villela not done any justice for Fritz Lang’s intended version of Metropolis, he has conformed to the stereotype of the blogger as an ‘amateur’ and has not championed the format of the blog as being something truly unbound and full of potential: ‘The best blogs are defined by this quality: they occupy a space between journalism and academia, between disciplines, between film and other cultural forms, offering a new type of criticism’ (ibid, p.19).

Postscript

This analysis was produced as one half of a film reviewership assignment and, as such, you can also read the companion piece - an original film review that I authored: Little Girls and Their Daddies: A Review of Lynn Ramsay's Gasman

Bibliography

Newman, Kim ‘Remake Remodel’. Sight & Sound, 20, (10), 2010, pp. 16 – 20.

Villela, Bernardo ‘The Complete Metropolis (2010)’, 2010. [Online] Accessed from: http://filmsnobbery.com/movie-reviews/the-complete-metropolis-2010/ [Accessed 16.11.2010].

Filmography

Metropolis or The Complete Metropolis (film); Fritz Lang. 145 minutes. Germany: UFA, 1927, re-release: 2010.

Blade Runner (film); Ridley Scott. 117 minutes. USA: The Ladd Company, Shaw Brothers, Warner Bros. Pictures, 1982.

Brazil (film); Terry Gilliam. 132 minutes. USA: Embassy International Pictures, 1985.

Avatar (film); James Cameron. 162 minutes. USA: Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, Dune Entertainment, Ingenious Film Partners, 2009.

Villela, Bernardo ‘Why a New Cut Matters’, 2010. [Online] Accessed from: http://filmsnobbery.com/blog/why-a-new-cut-matters/ [Accessed 17.11.2010].

Corrigan, Timothy J, A Short Guide to Writing About Film. Westford: Pearson Longman, 2007, pp. 1-17.

Buckland W Teach Yourself Film Studies, Hodder and Stoughton Education, 2003, pp154.

Fisher, Mark ‘Who Needs Critics? On Critics: Bloggers without boundaries’. Sight & Sound, 18 (10), 2008, p.19.

No comments:

Post a Comment